Following on from yesterday’s blog on organic farmer Dick Roper’s experiences of TB, badgers, selenium and maize I have been investigating the situation further. I have a friend Elliot Haines who is 5th year medical student at the Peninsula Medical School in Exeter and we have been discussing tuberculosis (TB). He has found some interesting papers regarding human health, TB and selenium.

For example a paper states that people with TB have lower selenium levels compared to those who don’t have TB – see here. This paper suggests that people with TB (and HIV) who have been given vitamins and selenium show improvements in their health. Another paper also reports an improvement in patient’s health who are suffering from TB when they are prescribed selenium – see here. Selenium levels is clearly playing a role in human health and TB.

Interestingly the Farmer’s Weekly and farming academics have published articles stating that many areas in the UK are selenium deficient and that this is an issue for agriculture and human health. – see here, here and here.

Below are three maps – they are not at all conclusive but they are worth investigating further ….

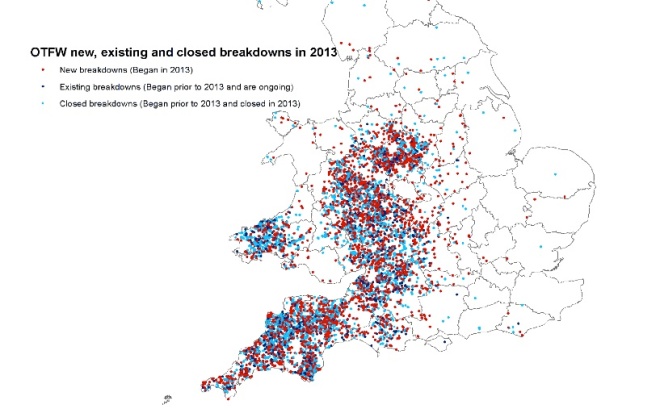

TB breakdowns in cattle herds in 2013 (note light blue dots are ‘closed breakdowns i.e. not TB in 2013)

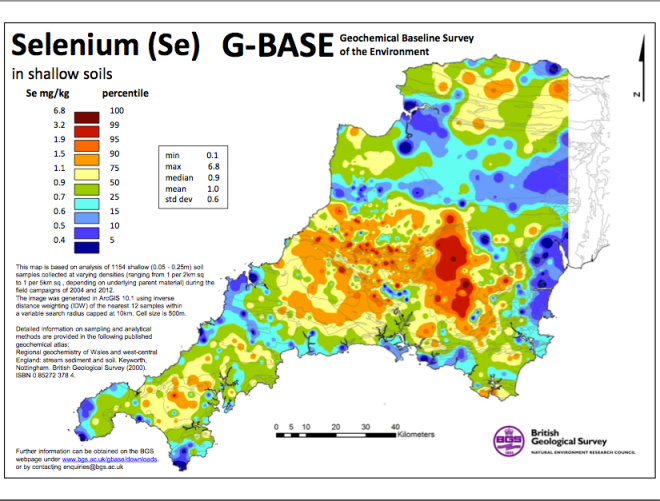

This is the British Geological Survey map of selenium levels in the south west – red = lots of selenium, blue = little selenium

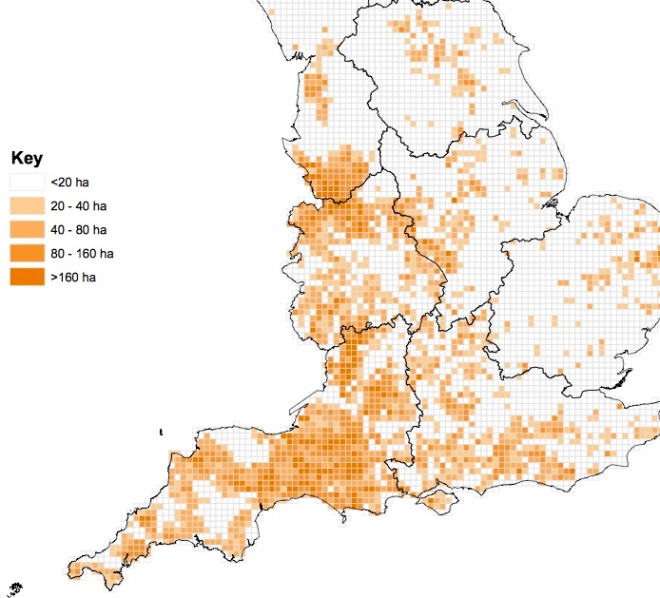

Here is the map of maize in the SW in 2010

Here is the map of maize in the SW in 2010

I really don’t want to get into pseudoscientific analysis and conclusions but this is all very interesting – some high moorland areas of Dartmoor for example have high selenium levels, low maize levels and low TB levels but do have populations of badgers and cattle. The analysis of the maps the maps off Dartmoor is more complex and would be worthy of detailed analysis.

Questions that I would like answered are:-

Is TB more prevalent in areas where selenium levels are lower?

Is TB more prevalent in areas where maize growing is more prevalent?

In areas where selenium levels are lower, does the growing of maize increase the threat of a TB outbreak?

Would some experimental work on supplementary feeding of badgers with selenium reduce the incidence of TB?

It would be interesting to know if all farmers who feed maize to cattle or are in areas of selenium deficient soils supplementary feed their cattle

The science seems to be saying

those (humans) with a selenium deficiency are more prone to TB

those (humans) with TB who are given selenium make more progress in recovery than those are aren’t

So maybe we ought to be researching this great deal more. As per my blog of yesterday, along Mr Roper’s experiences, should we be feeding selenium supplements to badgers to see what happens?

None of this is new but sadly we haven’t made enough progress – here are a couple of links to evidence Dr. Helen Fullerton made – the first in 1999 on this topic to a House Of Commons Select Committee – see here and here.

The National Trust has done some brilliant work on badger vaccination against TB on the Killerton Estate – see here. Adding in a ‘selenium element’ via supplementary of feeding of badgers with ‘selenium molasses’ would to me seem logical – it may show that it is not a factor but imagine the impact if it was conclusive! It would be cheap to do and be very useful in the overall debate.

So the hypothesis which needs to be tested is:- would supplementary feeding of badgers and cattle with selenium lead to a reduced incidence of TB outbreaks in cattle?